Preserving films from the 1930s takes time

Edge codes, the plus sign and square, tell us that this 16mm Kodak film from the A.E. Douglass collection was made in 1935

This past spring, the University of Arizona Libraries Special Collections was awarded a prestigious Recordings at Risk grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). Assistant librarian and archivist Trent Purdy and archival assistant Amanda Howard, the principal investigators for the $39,175 grant project, are digitizing and preserving 90 motion picture films from the collection of dendrochronologist Andrew Ellicott Douglass.

Douglass was the founder of the University of Arizona Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research (LTRR) and the "father of tree-ring dating." Dendrochronology is the dating and study of annual rings in trees. His recordings document his research in astronomy, climate science and the tree-ring record.

The $39,175 grant supports digitizing the films to create primary source materials. Special Collections will then make these materials available to researchers in all disciplines to support their research in the future.

In their own words, Trent and Amanda walk us through the process they used to preserve these films.

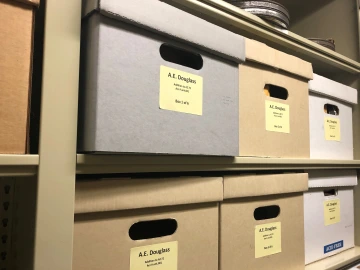

Starting with the boxes

Some of these 16mm and 35mm films are nearly 100 years old—spanning a 30-year period in Douglass’s academic career—from the mid-1920s to the mid-1950s. Before the films came to live in Special Collections in the early 1990s, they were stored in the LTRR, which was located on the west side of the Arizona Stadium. The LTRR is now in the Bryant Bannister Tree-Ring Building.

Storing the films in Special Collections allowed them to be held in a climate-controlled area, but these photos showing the contents in the box give a sense of the conditions.

We found a hodgepodge of loose film secured with string or in original box mailers from the 1920s and ’30s, along with film in rusty cans and on rusty reels. This isn't unusual for audio-visual collections in archives.

They require special enclosures and storage precautions. Specialized archival training is another requirement to properly care for AV materials. Most archives simply don't have the capacity for these expensive resources.

Prior to applying for the CLIR grant, we needed to do an extensive process of inspection to assess the condition and level of deterioration of each film.

Inspecting and assessing the films

Beginning in the spring of 2018, we used some tools of the trade—a rewind bench, guillotine splicer, and A-D strips—to perform this delicate work.

Other tools included split reels, an archival film core, gaffer’s tape for sealing canisters, a loupe, gloves, a pen for labeling the leader, archival canisters, and a film leader.

A-D strips, which look like think blue strips of paper, measure the level of degradation of cellulose acetate film based on acidic vapor produced by the item. The breaking down of acetate film produces a vinegar-like odor, giving it the name, "vinegar syndrome."

A-D strips are sealed inside archival film canisters for 24 hours to sample the amount of acetic acid being off-gassed by the film.

They change color—a range of blue to yellow—in the presence of acetic acid, and are read on a scale from 0-3. The greater the acidic reading based on the color of the strip, the greater the deterioration of the film. A process of rapid deterioration known as autocatalytic decay accelerates exponentially at a reading of 1.5 and above.

Of the 90 films in the Douglass papers, around 30 registered an A-D strip reading of .50 to 2.50. The remaining 50-plus films in the collection registered a .25 A-D strip reading or below.

One of the films turned an A-D strip lime green, registering a reading of 2.0. As archivists, that told us, "Bad news. Freeze me quick!"

Post-inspection, films are packed into canisters and protected with acid-free tissue paper.

Freezing in Arizona

The deterioration of films reading at .50 or above can be slowed by placing them in frozen storage. Film is sealed up in an archival can and two polyethylene bags before freezing.

Special Collections has its own frost-free freezer for just this purpose. However, when the time came to send the films off for digitization by our vendor, a run-of-the-mill household refrigerator was repurposed as a staging area to slowly defrost the films before they were ready to be packed up for travel.

Two days later, we packed up the films and shipped them off to the lab at The Media Preserve in Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania.

Prior to shipping the films, we created descriptive metadata in the form of Excel spreadsheets. The first spreadsheet contained descriptive metadata using a combination of Metadata Object Descriptor (MODS) and PBCore elements.

MODS is a metadata standard developed by the Library of Congress for library assets of all kinds, while PBCore is a metadata standard developed by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to be used specifically for audiovisual content.

Each of these allows for uniform, consistent descriptors across items, e.g. title, genre, language, and date. Descriptive metadata is generated to improve researcher discoverability and accessibility of content as well as preservation of both the physical films and corresponding digital surrogates. The second spreadsheet contained descriptive metadata, which is embedded into the preservation (.mkv) and access files (.mp4). Embedded metadata ensures long-term preservation of digital files.

Preserving your audiovisual keepsakes at home

In celebration of American Archives Month in October, here are a few tips we want to share with you.

If you have motion picture film, or any audiovisual media, you want to protect at home, the words “store in a cool, dry place” apply here.

- Handle your items with clean (or gloved) hands and always hold any media by its edges. Don’t touch the surface where information or images are recorded.

- Keep media away from changes in temperature and humidity, as well as direct light. No basements, attics, or storage sheds!

- Always store your film flat, preferably in an acid-free, ventilated container away from dust and debris. Store other formats—VHS, audio cassette tapes, LP records, DVDS—upright like books.

This project is supported by a Recordings at Risk grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). CLIR is an independent, nonprofit organization that forges strategies to enhance research, teaching and learning environments in collaboration with libraries, cultural institutions, and communities of higher learning. The Recordings at Risk grant program supports the preservation of rare and unique audio, audiovisual and other time-based media of high scholarly value through digital reformatting.