Papers of Pierre Lecomte du Noüy

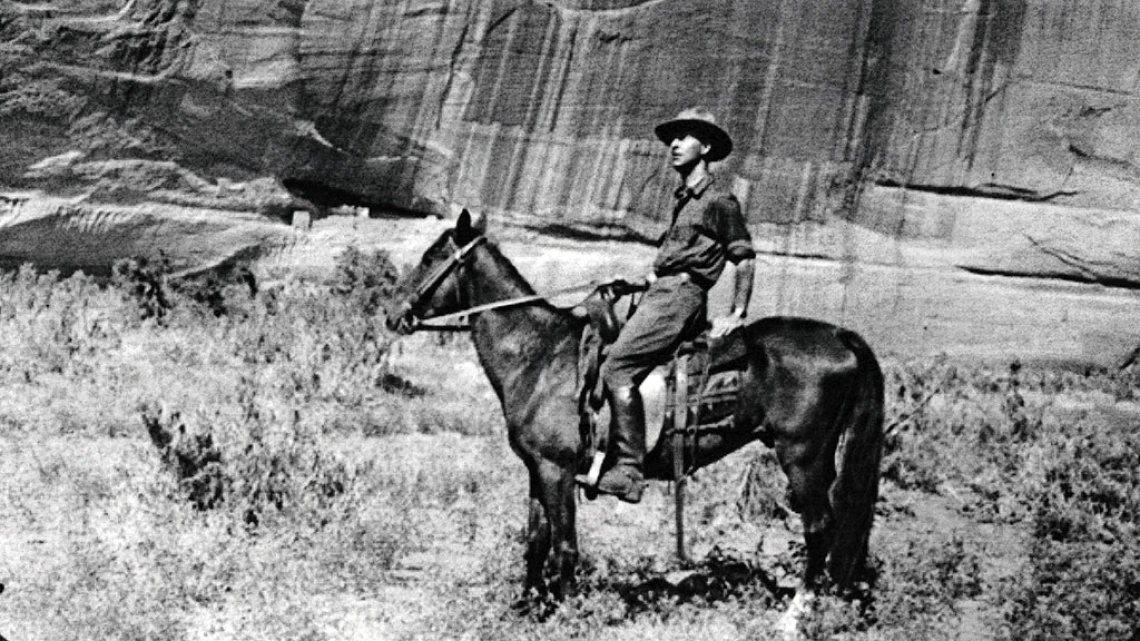

Pierre Lecomte du Noüy on horseback in Canyon de Chelly, AZ, 1922.

Collection area: History of Science

Collection dates: 1883-1972 bulk (bulk 1917-1949)

Scientific manuscripts, lectures, articles and lab manuals relate to Lecomte de Noüy's research in biophysics; performed chiefly at the Rockefeller Institute, New York, 1920-1927, and the Pasteur Institute, Paris, 1927-1936. After 1936, his writings concern philosophy of science; specifically as it relates to evolution, religion, and teleology. Manuscripts present include

Some materials are in French.

French bio-physicist and philosopher born in Paris on December 20, 1883. He obtained his degrees of LL.B; PH.B; SC.B; PH.D; and SC.D at the Sorbonne in Paris and graduated from Law School, though he never practiced. A descendant of writers and artists, who included Corneille, he was brought up in free thinking, intellectual circles and started life by writing short stories as well as several plays which were produced with success. His deep interest in philosophy and the belief that to progress, it would, henceforth, have to be based on science, led to his taking up his scientific studies again under the Curies, Appell, and others.

The outbreak of World War I sent him to the front as a lieutenant in the "Chasseurs à pied" but his knowledge of mechanics and driving soon put him in command of a motor section with headquarters at Compiègne, where he met Dr. Alexis Carrel, with whom he worked in his spare hours on the problem of the cicatrization of wounds. At Dr. Carrel's request he was attached in 1915 to his unit where he remained until the end of the war, with the exception of a short mission to the United States.

In 1920 he joined the Rockefeller Institute in New York as an associate member, leaving there in 1927 to go to the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he created the first laboratory of molecular bio-physics in Europe. Heisenberg's theory of indeterminism, as well as the laws of chance, coupled with years of work on living matter by means of physical methods, had convinced him that life and the steady progress of evolution cannot be accounted for by modern physical laws and that materialism can no longer be based on science. His articles and lectures on the subject aroused the enmity of the left wing and forced his resignation from the Pasteur Institute in 1936. The title of Director of the Ecole des Hautes Etudes at the Sorbonne did not provide the laboratories necessary to contine his scientific work and after a trip around the world he wrote

Together with his wife, an American, whom he married in 1923, he escaped from Paris at the end of 1942, reaching the United States of America in January 1943.

Lecomte de Noüy's scientific work can be classed in four principal groups:

1915-1920--Cicatrization of wounds--He established the mathematical formula based on the surface of the wound and age of the patient and could thus calculate beforehand the exact date of cicatrizatiuon and scientifically check the treatments employed to deduce the physiological age.

1920-1926--Absorption phenomena of surface tension--The tensiometer which won a Franklin Institute award in 1923, enabled him to provide evidence of the existence of monomolecular layers which in turn disclosed three minima in the surface tension of sodium oleate and enabled him to clculate the three dimensions of the molecule as well as the dimension of the ovalbumine molecule and give a determination of the Avogadro number in excellent accord with previous ones.

Physico-chemical characteristics of Immunity--The study of thin layers of serum on water led to the discovery of a physico-chemical phenomenon not due to immunization and showed that the serum is constituted of asymetric prismatic molecules capable of being polarized in monomolecular layers.

1927-1933--Experiments made by heating serum at a temperature above 55 degrees Celcius. Showed an increase in surface tension, viscosity, rotatory power, rotatory dispersion, etc. Altogether twelve new phenomena were discovered, proving that serum and plasma are true solutions molecularly dispersed and not colloids as had been thought hereto fore. Most of these experiments were based on new insturments and new techniques, which have since been extensively used in scientific and industrial laboratories. Amongst these figure the tensionmeter, a microviscosimeter, an ionometer for the measurement of pH up to the 4th and 5th decimal points and an automatic spectrophotometer in the infra-red.

A collection guide explains what's in a collection. New to using our collections? Learn how to use a collection guide.

Collection guideAccess this collection

Visit us in person to access materials from this collection. Our materials are one-of-a-kind and require special care, so they can’t be checked out or taken home.

How to cite

Learn how to cite and use materials from Special Collections in your research.